Once upon a time is now: A Japanese report features a fire-breathing, LED Dragon Tower

Our magazine always tries to report to our readers the most interesting news linked to LED screen technologies. Today we are reprinting here the excellent in-depth report of Mr. Louis Brill, well-known US journalist, about the “Dragon Tower”. Louis Brill has been reporting the latest news from all over the world about LED screens and other interesting LED applications for years. His contributions to the magazine SignWeb are most professional from both engineering and journalistic point of view.

Once upon a time, a formidable, cave-dwelling dragon devoured the children in the village of Koshigo, Japan. Benzaiten. the White Goddess of Fortune, vowed to stop the slaughter. Having caused a great earthquake, she descended from the clouds and, through her good influence, stopped the dragon's murderous ways. With her appearance, the island of Enoshima emerged from the sea. Since then, the goddess, one of the seven lucky Japanese deities, has been venerated at the sea resort near Tokyo.

Because the goddess is often depicted with a dragon, the Enoshima Spa and Resort honored her with a high-tech, LED sculpture. The Dragon Tower, a formidable, audiovisual sculpture, comprises a set of matching. LED screens that form a symbolic dragon that encircles a 40-ft. tower.

|

|

| LED Dragon Tower spiral video screens | |

The audiovisual, entertainment attraction presents a 20-minute video show across cylindrical video-screens. Periodically, at its base, a separate, water fountain gushes up in sync with the video program. The tower's two dragon heads erupt in a fire-breathing finale.

Architect Kilhak Kunimoto, of Atlanta-based Kunimoto Architect Design Group, explained that the resort wanted to draw tourists and local visitors with a spectacular electronic display “that is expected to become an iconic, entertainment destination in its own right.” As a visual-entertainment offering, the Dragon Tower is the island's version of Las Vegas' Fremont Street Experience.

Scaling the curves

Another member of the Enoshima Dragon Tower design team, Stone Mountain (GA) Productions, conceptualized the wraparound LED video screens and also served as design specifier and system integrator for the entire project. Bob Daffin, Stone Mountain's CEO, characterized the tower's multimedia capabilities: “With its visual display presence, the tower functions in several ways to represent the Enoshima Resort, serving simultaneously as an advertising medium, a special-event promotion platform and an entertainment attraction, all designed from a single, visual display package.”

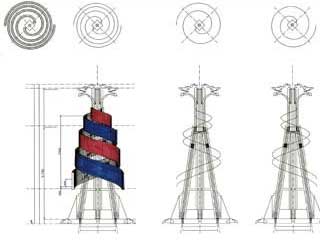

To fabricate the dual, spiraling, video displays. LED sign manufacturer Optec Displays (City of Industry, CA) transformed the screens into a practical, video display system. Bill McHugh, Optec's vice president of sales, explained that the unique project, which he believes is the first of its kind, posed many design and fabrication challenges.

“For example,” McHugh said, “we were concerned with how we would wrap an LED video screen 720° [each LED screen wraps two times] around a cylindrical tower. In doing that, we had to discover the video cabinets' geometric form as they curved upwards around the tower structure. We were also concerned with how the LED video modules would physically line up in proper x, y coordinates, despite the ascending spiral path they formed as they encircled the tower.”

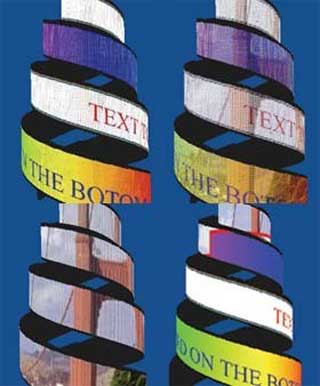

Optec also explored how to map a conventional video file into an equivalent format that could appear on spiraling video screens. To display images on curved screens. Optec corrected the image distortion. “Finally,” McHugh said, “we optimized the LED screens to allow video scenes to appear in one of two formats; either in their entirety across both screens, as a single image, or to appear simultaneously on each LED strip and then spiral up the tower as two separate messages.”

As McHugh observed, with no established, design precedents, the Dragon Tower's cylindrical screen was invented from scratch. To initiate this challenge, Optec took the conceptual ideas of Enoshima Resort and Stone Mountain Productions, and transformed them into a realistic, video display system.

To ensure high brightness and razor-sharp contrast, Optec relied on its LED hybrid pixel as the main building block of the video modules. Each 16 mm, LED unit comprises five diodes (two red, two green and one blue) per pixel. In this design, each pixel is totally encased in its own housing unit, and each unit is independently potted and sealed for complete weather resistance against the island's corrosive salt air. A series of fans keeps each cabinet's electronics within an operational temperature range.

To ensure maximum brightness, each pixel contains individualized, light-fitting louvers, which separately cover each LED. Additionally, because no Lexan ® polycarbonate lens covers the display face, the high-brightness levels allow audiences to see video shows despite the sometimes drastic viewing angles of the curved video screens. The high-brightness LEDs enable the screens to be visible during the day and evening. The surrounding, architectural lighting helps illuminate the Dragon Tower during spectacular night shows.

The initial engineering of the video display having been completed, a prototype comprising 12, LED video modules was tested at Optec's California research and design center and reviewed by Stone Mountain Productions and Optec software engineers. Working with the operational prototype, Optec engineers simplified the video module's design and wiring harness, and improved the LED band's curved shape. The prototype also allowed Optec to test the Dragon Tower's specialized, video-insertion software.

|

|

| Two spiral LED video bands of Dragon Tower | |

Placement of the two, interleaved, LED video bands around the tower structure posed the next design and engineering issue. McHugh said traditional, rectangular, LED video modules didn't fit properly. “By tiling the video modules upwards along the curve,” McHugh said, “the top edges created an undesirable, stair-step effect, which caused a 17°-pixel extension from video cabinet to video cabinet as they wound around the LED video band.”

At first, Optec thought the architectural cladding, which had a “scaled” appearance, would hide the modules' uneven edges. The cladding idea was then substituted by a geometric solution, in which Optec transformed the LED video cabinet into a parallelogram. The parallelogram's sloped surface allowed a flat-topped finish on the top and bottom cabinet surfaces. To attach the video cabinets to the tower, a cylindrical steel frame was welded around the tower, allowing the LED video cabinets (184 per video band) to be tiled, side by side, around the steel frame.

Software management of the video image and text-message files, so they were properly displayed on the curved surface, presented another, equally critical challenge. Optec software engineer Pavel Bonev discussed how flat, 2-D graphics were successfully converted to appear on the curved, parallelogram video screens.

“We solved this issue by creating two specialized, software programs for 3-D displays,” Bonev said. “The first program transforms the LED pixels' position in a 3D space to coordinates in a 2-D, rectangular stencil area created by unwrapping the banding, LED cylinder around the tower.” Depending on the unwrapping method, this software generates the 2-D stencils used by Stone Mountain graphics designers to prepare the signs' video pictures, and text and graphic content.

Bonev explained that, if each spiraling video screen was unwrapped, you would have an equivalent, elongated, linear band, which becomes a “video insertion stencil.” Such a stencil contains pictorial information about the relationship between each LED pixel from its 2-D, conventional-screen position to its equivalent, 3-D position on the tower's linear LED band. Ultimately, the transformation program correlates the video file's appearance on the spiraling video screen.

The second software package, a preview program, offers what-you see-is-what-you-get (WYSIWYG), real-time simulation of the video content on a 3-D, virtual model of the tower. This allows Stone Mountain Productions, the video-content designer, to see what the audience will see (the virtual model can be seen from any point of view), in advance of the actual video show launch on the Dragon Tower.

Fired up

The finished Dragon Tower now presents a complete, entertainment attraction for the Enoshima facility. Kunimoto said the tower, which is just being introduced, has yet to realize its potential as an attraction. “We have our first, complete show that we present on a daily basis,” Kunimoto said, “and we look forward to developing other shows in association with Stone Mountain Productions for specific Japanese holidays, such as Golden Week and Empire's Day. We also anticipate a New Year's Eve count down, similar to the end-of-the-year, Times Square celebration.”

Stone Mountain's Baffin said the tower's stunning premiere as an OLit-of-home, audiovisual experience “falls in line with the new trend towards experiential-marketing displays for retail malls, lifestyle and entertainment centers, and hotel-resort centers.” Optec's hybrid-pixel video screens' flexibility, coupled with Kunimoto's and Stone Mountain Productions' architectural elegance, has pushed LED spectaculars further into the public realm. As an LED video display, the Dragon Tower presents a new era of outdoor signage, which combines art and architecture as a public-communications medium.

Louis M. Brill - is a journalist and consultant for high-tech entertainment and media communications. He can be reached at (415) 664-0694 or louisbrill@sbcglobal.net